We need to talk about your cat because your cat is pissing me off.

Your cat is eating my socks. No. Really. Your cat has eaten four pairs of my socks.

Yes, I know cats can’t digest cloth. Your cat does not have super-feline sock-eating and digestion skills. Your cat nibbles the toes off my socks and then throws up these toe parts all over my closet floor as little gooey sockballs.

Your cat is pissing me off and we need to have a conversation about it.

The Topic of Conversation

In How to Run a Meeting, I describe a conversation as “verbal ping pong… you bat the little white verbal ball back and forth until someone wins”. This describes a simple conversation, but conversations are rarely simple. They have a variety of structures that are carefully negotiated and molded by the participants.

To understand the different type of structures, we need to define a base unit of conversation and the actions that potentially surround it. Let’s call this base unit of conversation a topic.

A topic is the headline you’d give to the current content and state of the conversation. Examples:

- The problem with our bug queue.

- I can’t stand Stan.

- You are bugging me in indescribable ways that I will now attempt to describe.

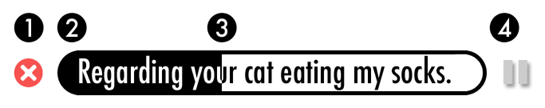

In my head, a topic looks like this:

The key parts of this model are:

- Stop button. For any number of reasons, a conversation can stop or be interrupted. When this occurs, all conversation participants are effectively agreeing: “This topic is done and there will be no further discussion during this conversation”.

- The agreed upon Topic of the conversation.

- Progress Bar. This is a totally subjective measure that indicates how close a conversation is to being resolved. If the bar is moving, this topic is currently in play.

- Pause button. A healthy conversation is rarely only focused on a single topic. Conversations meander from one topic to the next. When paused, a topic is no longer being discussed, but it remains open and unresolved in the minds of the participants.

This is a lot of preamble to describe an act we do automatically. If this model strikes you as overly complex, know this — you are going to spend half of your goddamned life suffering through the alignment of differing perspectives in any given conversation. It’s the single biggest waste of your time in dealing with other people and the better you understand, the less time you’ll waste. So, let’s circle back to…

Your Goddamned Cat

As we sit down to have our conversation regarding the sockballs littering my closet floor, I’m thinking about how I’m going to successfully convince you to keep your cat on a tighter leash. In fact, I don’t want the cat in the house at all, but you pay half the rent and we did agree when we arrived that the cat was cool. I need to figure out how to verbally amend that agreement, which means we’re going to need to negotiate. I’m going to have to concede something in order get the goddamned cat away from my delicious socks and out of the house.

In this case, I don’t know what my concession is — it’s something we need to discover via our conversation, which means there are a couple of potential topics:

- Regarding your cat eating my socks.

- The cat eviction negotiation.

- Things I know that piss you off.

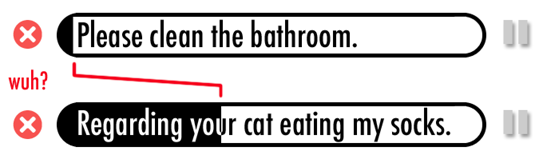

With these topics in mind, our conversation starts gently, in the living room. I explain, “I would like to discuss the matter of your cat eating my socks,” to which you respond, “I am sick and tired of you not cleaning the bathroom”.

Whoa. Wait. What?

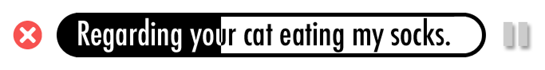

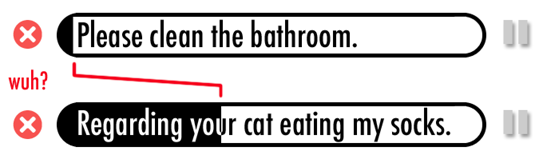

In my head, the conversation looked like this:

But you just hit the pause button on our first topic and started another topic:

The second topic introduces a new element in the model — the segue. This handy line is the context that ties one topic to another, which, in the case of the sockball situation, is currently a confusing, “Wuh?”

The point: it takes at least two people to have a conversation, but the real work is in making sure you’re both having the same conversation.

I can help.

A Conversation Structure

In computer science, there’s a concept called data structures. The idea is that a data structure is a model used to organize data so that it can be used efficiently. One of the simplest structures is called a list and it looks like this:

In terms of a conversation, think of lists as the most basic and easy to follow type of conversation. Using the model I describe above, no topic can be paused or stopped until the topic is resolved. There are no segues, tangents, or sidebars.

You’re thinking conversations as simple and structured as these don’t exist, and you’re right. This type of meeting does occur, but it’s called a presentation — where the speaker is click-click-clicking through his topics on his merry way towards the undisputed end.

While this basic list of conversations doesn’t exist, there are people who want them to exist and will make this clear as part of the conversation. They sound like this:

- “Wait, wait, wait, we’re not done with topic #1. Can we talk about topic #1?”

- “Hold it, before we go there, what about the issue at hand?”

- “This new topic has absolutely nothing to do with what we’re talking about.”

The intricacies and implementation of various data structures are not the topic of this article. What’s relevant is understanding that there are different conversation models you might find yourself in and then figuring out how to adapt.

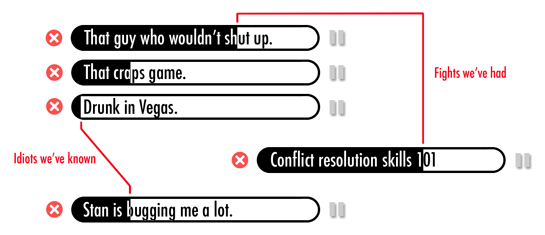

The Stack

A slightly more complex data structure, and one that is more representative of a real conversation, is the stack. This is where our Pause and Stop buttons come into play. Let’s go back to that goddamned sock-eating cat to understand. Our conversation started with the sock topic, but you immediately put a Pause on that first topic and fired up a new one. In my head that looks this:

This is a stack. The topics are literally stacked on top of each other because, in my head, we’re actually talking about both topics, and the successful conclusion of all topics is key to this entire conversation coming to a successful conclusion. The question is are we both prepared for this type of conversation?

My definition of an effective conversation is if, at any moment, you could ask any participant in the conversation to point at precisely which topic was being discussed and how that topic was progressing. Bonus points for walking through the stack and explaining how you got there.

When conversation participants lose the context of the conversation, when they lose track of where they are, they stop listening and stop participating. The conversation no longer has a chance of resolution because resolution requires their active involvement and all they’re doing is fake listening to your speech.

Conversation Tolerances

A stacked conversation, one with multiple topics tied together with segues, is where everyone involved needs to keep track not just of the complexities of the conversation, but of the tolerances of those participating. Again, this is not a meeting with a well-defined agenda and anointed leader; this is a conversation where everyone needs to keep their wits about them.

When a conversation gets complex, this is what I’m watching for:

How many open topics can we handle? Each segue moves us slightly further from the starting topic. Are you cool with that? Ok, how many topics can you keep in your head? There’s a point where everyone will lose track of where they are if we have too many open topics — what’s your threshold? Wait, now I’m lost, so I’m going to ask: “How’d we get here?”

What’s our segue tolerance? How deliberate do I need to be switching from one topic to the next? Do I need to explicitly say, “We are switching topics now,” or can you keep up? How much segue detail do I need to give? Can anyone hit Pause and pivot to a new topic? Will you? Ok, you just did, but I don’t understand your segue, so I’ll ask: “Please explain how this relates to that.”

What’s our closure tolerance? How much progress do you need to make before we switch topics? Will you get cranky if we don’t even try to resolve something? Is this topic more important to you than other open ones? Will you freak out if all is not resolved? Can the conversation totally mutate into something else? Is that a bad thing?

Understanding both your own conversation tolerances as well as the ones of those you converse with is essential to having a successful conversation, and the best way to know where they’re at is to look. Humans wear a bevy of visual cues that indicate their comfort with a conversation. Nods, sounds, and eye contact — these are potential signs of engagement. The rule is, if they look lost, you ask: “What did you just hear?” If you’re lost, you say: “I’m not following you.”

The Tree

Problem solving is the art of a finding a solution acceptable to everyone in the conversation. If everyone knew the solution to the problem, you wouldn’t be having the conversation in the first place. If there is no problem, then, well, you’re shooting the shit. Problem solving means getting conversationally creative, and being creative means letting yourself mentally wander — eschewing structure. This is why my favorite conversation structure is the Tree.

The Tree is the pinnacle of advanced conversations. Where a stacked conversation looks like this:

The tree appears chaotic:

The simple explanation of the Tree conversation is that it’s multiple conversations. In the image above, you’re looking at three seemingly disparate conversations, except they’re not. The reality and the definition of the Tree-based conversations are the inspired segues. Think of a conversation with your best friend. Would anyone listening to this conversation actually be able to follow it? Could they diagram it? Of course not.

Could you? Of course.

For qualified participants, the Tree is pure conversational joy. Topics vary wildly, being held together by only the thinnest of segues that are often unspoken, but there is a structure. And more importantly, there is mutual understanding and appreciation of this wonderfully chaotic verbal mess, because it’s in this mess where you have the most potential to resolve the topic.

Remember, this is a conversation; it’s not a story and it’s not a meeting. There is a topic to be resolved and no one is happy until that topic is resolved. If this was a trivial topic, if we could just tell your cat to stop eating my socks. Resolution might be easy, but it’s not. My spoken frustration about your sock-eating cat has triggered your response about my inept cleaning skills, which means now we’re going to do some heavy-duty roommate therapy.

The resolution might be tricky and it might involve verbally wandering to disparate topics, but you and I have known each other for years. We’re ok with a deep stack of topics that eventually transform into a forest of conversations. We know that part of big discovery is verbally wandering into strange mental places.

Was this a topic you wanted to write about, and you just hit on the sock-eating cat as a conversational hook? Because this sounds like the most passive-aggressive move I’ve ever seen for yelling at your roommate. One I wish I’d thought of first.

Wow.

A very comprehensive analysis of conversation chaos.

Very interesting explanation of something that happens to me every day without thinking about it.

Thank you!

I would cite the “The Magical Number Seven” rule to define the average number of conversations that you can have at a single time. Means that most people can think of between 5 and 9 things at once. With this addition you can site the use of a common UI rule along with data structures. btw, i love the blog.

Generally, I try to keep one meaningful topic of conversation per person involved in the convo; the more people, typically the fewer segues can be maintained (people are waiting to get back to their own stuff and their minds wander).

I define interactions as transactional in nature; with your examples above, you and your roommate are both trying to get a finite result out of the conversation. If, wandering into the convo, you can define what people want, you can help alleviate tension by bringing that out in the convo and negotiating those things.

Usually, though, straightforward understanding of what is to be got out of a convo just isn’t there; you don’t know who that person was talking to before you, if their boss just reprioritized their entire work life and they are still reeling, or if they heard a song on the radio that reminded them of that girl they met on the beach two years ago and are now in a seriously bad temper since on FB they know she’s getting married.

Even if you’re hanging with friends and shooting the breeze–say, complaining about how the IT department is totally not getting you the new memory you need for your dev server which is really slowing down the efforts–you’re getting something out of the convo. Venting, happiness, distraction…these are also applicable goals.

Where knowing the goals really matters, however, is in conversations where not knowing them involves potential land mines. Thinking a convo with your boss is about venting when the boss thinks its about information gathering will explode when you lift your foot up.

So, tracking the various conversations, who is attached to what, and maintaining a reasonable level of attention from participants is very important, I think, also, making some estimates about what people are trying to get out of the conversation can save you a lot of grief down the line (and maybe help you).

Put your socks away.

This is a great model of the kind of conversations used to solve problems. But the most important conversations (IMHO) are ends-in-themselves. Examples are connecting, flirting. Lori’s examples are good: venting, [conversation which results in] happiness, [conversation used as a] distraction. Your model totally fails for this type of conversation which, for me, is like 80% of my conversations.

I would be really interested to see if you can model these!

Conversation as combat versus Conversation as pleasure seems like a great way to talk about the so-called 80/20 rule.

Conversation is 20% argument, 80% social lubricant?

@Sarah: In our household, we try to not let pets dictate how we manage clothing. Besides, our cat will attempt to eat your socks while you are wearing them. Part Egyptian Mau, y’see.

I agree with Matt about stack depth, except I think even five is pushing it.

My alarm goes off according to interruptions per attempted topic, especially those interruptions prior to The Point. It’s not the tree depth or the level of antagonism; it’s something more basic about respect, willingness to listen. Too many interruptions and I’ll manually reset the conversation… not fun for me but it seems to work.

(In this, I assume people who know how to either tell a good story or reach The Point quickly. Blowhards are a different issue.)

Cool post, I love how the title triggers an aggressive response, and then it softens down into to an understandable issue. Thinking of conversations in terms of data structures is great, I’m gonna try that next week!

@maggiel In my household we like to solve problems that occur. If we refuse a simple way of solving the problem, then maybe it was never the real problem at all. A conversation about stopping a cat eating socks is not going to have a successful outcome if what we really want is to get rid of the cat. Coming up with lame reasons why we couldn’t solve the problem ourselves (not engaging in what would be a normal piece of household cleaniness for most people because that would somehow be letting the pets dictate) shows we’re entering into the conversation in bad faith, the other participant is on a hiding to nothing, and our real problem is unlikely to be fixed (at least until we’ve created such a hostile atmosphere that one party moves out).

If you have a problem with the way a colleague communicates in email, telling them you don’t like the typeface they use is not going to resolve the problem.

@ Sarah

I am sick and tired of you not cleaning the bathroom.

You’ve left out a conversational data structure that is highly favored by my wife’s family. Multithreaded (with work stealing).

One of the points that stand out for me is:

The point: it takes at least two people to have a conversation, but the real work is in making sure you’re both having the same conversation.

I observe people discussing different points, sometimes vehemently, many times a day. It is always a pleasure to reconnect the participants, but not always appreciated.

Do you have tips to share in this regard?

because of the delays in online textual chat, my wife and i used to run three linear conversations regularly. in an odd way, it was like a conversation among six people.

Clearly the cat is eating socks that were left on the floor in the bathroom along with other detritus. It’s rather sweet of him to return the remnants to the owner’s closet.

My spouse and i ended up being absolutely glad that Jordan could do his researching while using the precious recommendations he was given in your site. It’s not at all simplistic to just possibly be giving out tips and tricks that men and women could have been making money from. And we also recognize we need the writer to appreciate for that. The type of explanations you have made, the easy website menu, the relationships your site make it easier to instill – it is everything unbelievable, and it’s aiding our son and the family feel that this idea is thrilling, and that is unbelievably serious. Many thanks for the whole thing!