I’m at the end of a conference week and I’ve just moved hotels. This is normally a hassle, but the broadband in the prior hotel blew, which means I’m a week behind on everything. Once I’ve checked into the room, the first thing I do is fire up Safari and watch the first page load. Nearly instant.

Sweet, sweet broadband.

As we know, high-speed access to the Internet is the key to information bliss in The Cave, but we’re not in our Cave, are we? We’re in New Zealand on the 9th floor of a strange hotel where they tell me the water flushes down the toilet in the opposite direction. I haven’t checked; I’m busy building my Cave away from home.

There are two goals with the process: creating a sense of comfortable familiarity while also managing the interestingness of the surroundings. I start by positioning the desk so I have line of sight to the TV, and then I remove all non-essential, distracting crap from the surface. I turn on the desk lamp and the bathroom light and turn off the rest of the room lights, creating a comfortable blanket of darkness around the desk.

The window stays open unless it’s a significant source of glare. I used to always pull the drapes because I used to see windows as very high-resolution screen savers, which are apt to grab my attention. But, as we’ll see, the interestingness of this natural screen saver outweighs the risk.

Lastly, I need mental background noise to tap into when I’m not focusing on whatever task it is I’m working on. Back at home, my favorite source of white noise is the coffee shop. It’s chock full of people, stories, and familiar, random sounds that fuel my creative forward momentum.

No coffee shop here, so I need to create it. A movie will work, and I get lucky and find Casino Royale, which I’ve already seen.

I spend the next hour and a half doing tasks that don’t require significant attention. I’m scrubbing email, scribbling random thoughts, triaging bugs, tidying articles in progress, and generally doing tasks on the B list. What’s more interesting are my mental breaks. I jump into another tab in Safari and take a glance at del.icio.us, Digg, Google Reader, or other meta-content. I watch the movie for a few moments or glance out the window to see what the world is up to.

These mental breaks share a common trait: they provide rich content, but not rich enough content that I’ll stop working on my B-list tasks.

When Casino Royale is over, the next movie comes on, which is The Majestic, with Jim Carrey. This presents a potential problem. I haven’t seen this movie, and I don’t want to risk it being good and grabbing my attention.

No problem. Wikipedia to the rescue. I spend five minutes reading the plot of The Majestic and I’m done. The summary describes all the plot twists and aspects of the movie that might grab my attention. Reading the Wikipedia summary lobotomizes the interestingness so that the movie becomes structured white noise. I can glance at it for 5 seconds, take my mental content break, and not get lost in wondering where the movie is going because I already know how it’s going to end.

The World is Not a Screen Saver

In Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point, he describes how researchers for Sesame Street determined what parts and how much of the show were actually registering with five-year-old kids. What they discovered was that, when presented with toys and quality segments, these children were able to play with toys and remember content from the show just as well as kids who just watched the show.

This research from the late 1960s contradicts a lot of the bitch-slapping directed at multitasking, especially in the recent Autumn of the Multitaskers article. The article summarizes, “we concentrate on the act of concentration at the expense of whatever it is that we’re supposed to be concentrating on”. This article goes on to say that multitasking-related stress prematurely ages us, hampers our ability to focus and analyze, and, in the long term, causes our brains to atrophy.

Compelling stuff. I especially like the reference to one of the studies where “… researchers asked a group of 20-somethings to sort index cards in two trials, once in silence and once while simultaneously listening for specific tones in a series of randomly presented sounds.”

Knowing how important having a properly constructed Cave is to me, both at home and remotely, the phrase “listening for specific tones in a series of randomly presented sounds” stands out. Think about how the task of listening for specific tones amongst noise would fit into my Cave environment. The answer is: it wouldn’t. In fact, it would drive me batshit crazy and I’d chase the researcher out of my hotel room with a broom or whatever the hell they call a broom in New Zealand. Of course the students listening for tones in random noise learned less; the researchers were bugging the shit out of them.

The Autumn of the Multitaskers actually leads with a story about how the author crashed his car trying to use his cell phone while driving. He implies, but does not explore, the idea that multitasking is a skill and not a generational curse. The hidden contradiction in the article is that you could just be really bad at multitasking. And my guess is that being really bad at anything you need to do often is potentially a recipe for stress and early aging.

It also reminded me of another thing: I don’t multitask.

Multitasking is a convenient descriptive term for what I do. In fact, to the outside observer, multitasking is a perfect description, but because it’s based on outside observation, it’s misleading.

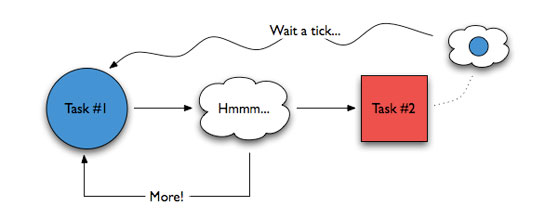

I don’t multitask. Think about it, you can’t concentrate on two things at once. Yes, to the outsider, I am doing many tasks at once, but in my head I can only do one thing at a time. Where the art is, where the skill is, and what the term should describe is what I do between the tasks. What I do well is a combination of timely, adept context switches combined with content-rich breaks. It looks like this:

And it feels like this.

I deeply consider the thing I’m working on. I sit up straight, furrow my brow, talk to myself, and dig into what I’m doing. My environment is meticulously designed to support this, whether it’s the precise, familiar location of my computer, the blanket of darkness surrounding me, or the white noise I select to provide a mental break focal point.

At some point while working, I will reach a mental block. I quickly assess the magnitude of this block (minor cramp or total fucking blockage?) against the priority of the task (need to finish this now or whenever?) Based on that lightning fast assessment, I either stop or grind it out.

This stop may be a context switch to another task, but it’s often a break to soak in the white noise, and it’s in these pauses that I’m brutally creative. When I stare out the window of the hotel, I see a small harbor full of sailboats, and, somehow, the haphazard arrangement of the colorful sails reminds me of a summer in Minnesota where my jerk of a cousin taught me to play Bloody Knuckles after everyone went to bed. Bloody knuckles, now that was a game, and games remind me of the bizarrely different ways human beings have figured out how to communicate, which is the EXACT topic I’m currently writing about, so I jump back to my MacBook and continue writing.

Or perhaps I don’t find my sailboat segue. Perhaps the harbor takes me in a different direction and I’m inspired to switch tasks. Fine, back to that email where I’ve been writing a response to a flame mail from a well-intentioned engineer who has suddenly realized that he’s been ignoring the web for five years. And it turns out the web has changed a bit and his five-year-old mastery of web technologies is now obsolete. His recent discovery of his irrelevance (cough: Fez) has turned into this flame mail, which requires a careful response. And, you know, email is just another bizarre construction by which we communicate AND HEY that’s the topic I was just writing about, so I switch back to my original writing task.

The actual elapsed time that occurred during the previous three paragraphs is about 10 seconds, including my five-second inspirational pace in front of window. And if you were watching me, you’d think, “restless, unfocused, multitasker”. What you can see now, with internal context, is that I’m really only working on one thing: the article about communication.

Yes, I almost made a switch to another task, extinguishing the flame mail, but even if I did, I’d still have the echo of what I was just doing. Tasks get messed up in my head, yes, but mixing shit up is how you build new shit.

Distributed Attention

Back to Gladwell’s research. What they learned was that the five-year-olds were “Attending quite strategically, distributing their attention between toy play and viewing so that they were looking at what for them were the most informative parts of the program. This strategy was so effective that the children could gain no more from increased attention.”

Multitasking is the art of distributing your attention and, guess what, you’ve instinctively known how to do it since you were five. What have you done since then? You’ve worried about information overload, you’ve devised a new way to get things done, and you’ve thought “That’s me!” when someone has taken the time to describe something you already knew.

Me, I’m watching how I context switch. I’m learning when I need to switch to a new task or just relate what I want to do with what I’m currently doing. I’m figuring out the right environment to seed my tasks and my non-tasks that push my ideas towards a coherent structure. At the same time, I’m acknowledging that documented excessive structure might sell books and provide misleading comfort, but it doesn’t provide much space for inspiration.

My Cave, wherever I build it, is a deceptively creative structure. I surround myself with creativity-driving, chaotic-seeming natural order, which is built with the understanding that I can only do one thing at a time, but when I stop, I create.

Thank you! It’s so nice to have someone else saying what I’ve been formulating myself. That way I don’t have to start from scratch when explaining myself, I can just refer others to this post.

I read your N.A.D.D. article when it first came out. Now, 5 years later, I have been officially diagnosed with A.D.D. I’ve been trying to communicate my idea of multi-tasking to others for a while now — a previous employer actually held it against me that I “didn’t believe in multi-tasking.” Those sorts of people won’t really listen to any amount of brain research you bring up, but at least I know that I’m part of the nerd group that is changing the world. Now to figure out my personal control panel . . .

Basically, it’s like computers running on a single thread. You can keep doing context switchings but you really can only handle one thing at a time.

I use podcasts for the same purpose. I recommend it over ruining movies you might eventually enjoy!

Lore Sjoberg recently wrote an article on the same or a similar phenomenon in which he uses a wonderful ferret metaphor to describe his brain’s needs, goes on to describe how he feeds his multivarious brain ferrets, and eventually asks for podcast suggestions.

http://slumbering.lungfish.com/?p=552

We call those things brooms here in New Zealand. :p

It’s funny, this multitasking thing. I know how terrible it is for getting things down. And yet I rarely find myself able to tear myself away from NADD. OK, done checking stuff out in Google Reader, alright time to get something done…I wonder if the Digg homepage has changed…oh I forgot an away message and now I have an IM–hours later I’ve gotten no where on my intended task.

What does it take to have the discipline to sit and accomplish a single task? Zen?

Music and movies are definitely high on the list of background white noise. Watching movies while doing homework and projects was how I got through college.

Hate to nitpick, but water going down a drain pays no attention to which hemisphere you’re in, that’s just an old wives tale. It depends size and shape of drain and the direction the water comes from.

As usual, an excellent way to put it. For my own patterns I add a DVR. I can tell when something worthwhile has just happened in a movie I’m watching for the first time, so I swap from my paper-writing/IRC/test-grading/IM/whatever and back it up a minute, watch the neat thing, and then back into whatever I was doing.

I’d say it crops up earlier than 5 years old. I’ve got a 13-month old son and he constantly multitasks. We can’t stop him. He walks around banging on things while he’s drinking milk from a cup. He fiddles with a toy while reading a book.

He’s definitely capable of very focused attention, but it seems like once he’s mastered some simple thing he gets restless about doing just that and nothing else … he’ll start wanting to combine it with something else. Sound familiar? 🙂

There are two things I’d like to add:

The first is that it really does feel more like context switching. I don’t know if I was born with it or taught it by the Internet, but the cost of context switching seems very small to me. Going from mail to movie to code to web is all very quick. And sometimes I can even throw in tracking the laundry and making dinner too.

The second is that sometimes it feels like there are different parts of the brain that need different forms of stimulation. For example, I have to be fidgiting or otherwise doing something when I talk to people. I like having a Rubick’s Cube near the phone which I can solve over and over, or a pen I can disassemble and reassemble. It’s like physical white noise. Add that to auditory white noise and I get my best thinking environment. If I can keep those parts of my brain busy, the higher order parts don’t get distracted as easily.

That was so much fun to read. The “mixing shit up is how you build new shit” bit is both profound and funny. Things that make you simultaneously think and laugh are some of the best things in life. Great post.

Thanks for that Rands, It was an interesting read. As many other’s have commented I too relate to what you’re saying. I found I could never study in the library, the silence was distracting. I needed a layer of noise to ignore and to soak up the mini brain breaks.

Glenn

I adore the irony of that sentence. 🙂

This is one of the best descriptions I’ve seen of how I work, and I imagine a lot of people in my generation (I’m 27) would identify with it on a similar level. It’s often hard to explain *why it works, but I’ve tried working other ways, and this kind of context-switching pattern is by far the most natural and productive. It’s nice to hear an articulate explanation (justification) for why I feel that way.

My boss used to remind me that I was easily distracted by ‘shiny objects’. These items were obviously not gold nuggets, but random shit that would pass my cubicle or pop up on my screen. I could be mid-sentence, and oops, there it goes. M attention diverted. I think it is a fact that even when appearing to be ‘multitasking’, we are truly only focusing on one thing at a time. Especially us N.A.D.D.ers. At work, I typically do quite fine working on various projects, but when the phone rings, I always mutter a ‘delete expletive’. Regardless, great insight.

Regarding the toilet water: the water going down the toilet in an opposite direction is purely a myth. The directionality of toilet water has more to do with the shape of the bowl and the level than the Coriolis Effect.

Heard your talk at SXSW today (the pencils are the wrong color… the blue is fine.) and greatly enjoyed it. Checked out your blog and this post really hit home. There’s a great Time Magazine article (time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1147136-2,00.html) about the financial cost of interruption. In it, the University of California at Irvine did a study of technology workers. Here’s a quote:

“Once they were interrupted, it took, on average, a stunning 25 minutes to return to the original task—if they managed to do so at all that day. The workers in the study were juggling an average of 12 projects apiece—a situation one subject described as ‘constant, multitasking craziness.'”

In a progressively addictive multitasking society, I can only find peace by working super late into the night. No one calls, texts or IMs. It’s my cave.

Another great read. And I think Rands hits the nail in the head once again. I’ve struggled for the past year or so because my interruptions have increased (workload is the same).

I didn’t realize until now that a good part of my issue is the setup of my cave. I can switch contexts quickly to work on different tasks, but the intruders coming into my cave are what cause my stress. Must seek a new cave.

Brains are weird. If you pull out e.g. Raskin, you find that we generally have about 5 conscious attention slots. Try it: List how many things you are actively ‘doing’ or ‘worrying about’ but discount anything that pops into your head *while* you’re listing — the *pop* means you just shuffled your working set.

This is often quoted and can be a serious problem when performing latency-critical tasks like piloting an airplane or car.

Now, it turns out we’re using a lot of the rest of our brain to maintain our map of the universe, from basic proprioception on up through emotion and knowledge. (This extrapolated in part from some findings in _The_Head_Trip_.) So if a “task” requires more creativity than latency, there’s a chance some neurons are “simulating” it whether or not we’re devoting the direct executive power of “attention” to it. We seem to have a mechanism, as humans, to keep creating hypotheticals, crunching the consequences, and, through messy biological mechanisms (combining both interrupts and polling), getting the results vetted “consciously.”

In fact, the simulation aspect seems to be how we interpret memories, while “attention” is the I/O layer, where we become aware of sensory input and formulate our output/response. But if we fail to poll either our senses or our memories, we can just plain forget about things, or respond based on an outdated model: Consider the distracted (or just plain bad) driver who resurfaces from [dialing phone | eating lunch | applying makeup] and starts to merge based on a mental model (a hypothetical) that missed its chance to include the car in his/her blind spot.

Now contrast that to the programmer or any other creative nerd working on a task that’s relatively latency-independent (aside from deadlines) and throughput-dependent (‘quantity of creative breakthroughs’ being the metric that results in completed work), in a fixed logical system that [normally] isn’t going to change by surprise. That sort of system can successfully be modeled, and if the nerd’s brain is a good enough simulator or emulator, it can be modeled reliably.

At that point it’s not helpful to stare at the editor watching for a tiger to pounce or the cursor to sneak up in your blind spot; what counts is keeping the simulations running until the goopy neural network has modeled the hypothetical approaches that can be sanity-checked and perhaps taken; that’s “imagination” at work.

It seems like both the short-term attention slots and longer-term memory and modeling rely on a sort of DRAM-like refresh — but since we’re meat, and meat is messy, we’re also refreshing the neuronal connections (the basic wiring, but figure pointers in a software analogy) to our relatively persistent long-term memories.

The “five slots” rule of thumb behaves sort of like a linked list, or a chain of ‘smart’ DRAMs where each has to contain instructions to refresh the next; grow the chain too long and short-term memory decays, get sidetracked and you’re filling the buffer with new I/O instead of remembering to check your mirrors or water the plants.

…

The trick is to know which tasks require “realtime” processing, know which ones you get equal or greater throughput on by doing something else (like using ‘background noise’ to inspire new hypotheticals), and have watchdogs in place so you remember to watch where you’re going and don’t forget entirely about tasks you’re letting bake, respectively.

…

The real problem, on the other hand, is that most of our technological distractions are now communications-based, and a lot of tasks that used to be polled (or “bakeable”) have become interrupt-based (IM, ringing cellphones, popups). We have a gut impulse to move to interrupts to squeeze more and more from our fixed lifespans, but there are two problems that result in gripes like the one discussed here:

1. People who can’t adapt to the distraction-rich environment, whether for real ADD or lack of skill, can’t accept these new extraneous interrupts as part of the ‘background noise’ and make “errors,” attending to the ringing cellphone and crashing the bus.

2. Primate neurology produces different responses to different scenarios; since time immemorial we were selected to associate throughput and sustenance, even back before agriculture — “got a lot of work done” triggers the same satiety and sense of well-being that foraging (or consuming) a lot of food did. Latency scenarios are governed more by other survival and panic responses; “did not crash the bus” conveys a different sense of relief governed by different chemicals.

We’re not used to measuring success in terms of “did not crash the bus,” and we have poor cultural mechanisms for rewarding it. (Since Dickens, being high strung has been the condition of the working class that has the misfortune of being replaceable, after all; we will, however, reward people greatly for massive throughput, as when celebrities release a blockbuster or upper management does something ‘important.’ We have an innate understanding of the risk/reward of those latter events — like when some monkey dared leap a ravine and found a banana grove — but we’re less used to rewarding someone for simply responding quickly or maintaining the status quo without having things go to pieces, even if it requires as much human effort.)

When monkeys were coupled by higher-latency links of equal throughput — note that information throughput for brain-work between individual humans has only increased a few times, with the invention of writing, the photograph, the motion picture, and the useful computer program, each requiring greater and greater effort to produce with acceptable quality — effort was under proportionally less demand; the deadlines were longer. The ability of human labor was also pretty much a fixed quantity until the industrial revolution hit, at which point the consequences of technology-augmented individual action ballooned like crazy. (Few people ever crashed the horse, and if they did they probably didn’t take anyone else out with them. We died of stuff like flu and plague and brainworms instead, but we weren’t worried when we couldn’t see it coming.)

The point? Being “successful” enough to maintain our standards of living (which the meat in our heads interprets as ‘survival’), and thus our relative satisfaction with our lives now requires adaptation to higher and higher frequencies of interruption, while our brains’ capacity for throughput has remained pretty constant. (What did individual authors use the once-ridiculous capacity of CDs for? Encoding the equivalent of an evening’s live performance, or encoding the ‘multimedia’ equivalent of a book with illustrations.) There are thus some good arguments that we’re spending more time geared up in our panic responses despite our improved standards of living and exciting new modes of leisure.

Oh, this is *so* me. And I get all sorts of people — like bosses — looking at me like I’m lazy or some shit because my screen is constantly flipping contexts. So what if my screen is on Safari and I’m reading something… it doesn’t mean in one of my other Spaces some app (or three) aren’t busy doing something on their own.

Do I make my deadlines? Yes? Then back the hell off. Just because you sit there and watch a progress bar for 15 minutes, it doesn’t mean *I* want to!

FYI Rand, you are one of my favourite white noise points, the break between the activities, not because it’s a blank but rather it is a nudge to the brain, a place to relax and come back stronger from. Creativity in a mental break.