I’m a hockey guy. Picked it up in college and spent the next two decades playing all forms of hockey: deck, roller, and ice. The Sharks arrived in San Jose and made my chosen sport official. I was set.

However, there were two sports before hockey. It started in junior high with cross-country running and followed by a summer of intense bike riding. My sixth-grade science teacher, Mr. Momberg, recruited me and would not take no for an answer after I demonstrated a tepid interest in his summer cycling club.

I’m a country mouse, too. Outside of the window right this second I can see oaks, bays, and redwoods… for miles. These trees thrive on the hills of the Santa Cruz mountains. Roads in various forms of disrepair cover these hills, and the cycling club biked everywhere: New Brighton Beach, Big Basin, Soquel, Aptos, Felton, Corralitos, and Ben Lomond. We finished the summer with a Century: a 100-mile ride over the course of a day. I couldn’t walk for two days. It was divine.

Mr. Momberg transferred to a different school, the bike gathered dust and then rust, college arrived, and then hockey showed up. While the physical calculus of hockey remains one favorite part of both playing and watching the game, there are not a lot of hockey rinks in or near the Santa Cruz mountains. Getting to the various rinks, playing three periods of hockey, and getting back is a three and a half hour process with only one of those hours being precious exercise.

My wife suggested biking in early 2014. Mountain biking specifically because we live in the Santa Cruz mountains. Right next door is the Soquel Demonstration Forest(“Demo”) which contains some of the best mountain biking in California and perhaps the planet.

“Yeah, sure, let’s get bikes.” So, we did.

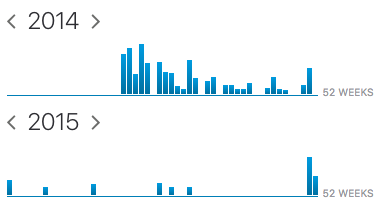

Strava1 records 2014 and tells the familiar and painful tale of my surge of interest in a new hobby. Peak interest followed by gradual decay. In 2014, I biked 427 miles over 52 hours. In 2015, I biked 116 miles over 15 hours. Interest clearly fading.

Alexa is the name of that first bike. A Specialized Camber. She introduced me to the wonders of good shocks on rough terrain, but she also stared at me from the garage for most of 2015 asking, “Bro, can we ride?”

We didn’t ride much. My riding guilt spilled over into the purchase of a second mountain bike. Mackenzie, a Santa Cruz 5010 with a carbon-frame and decreased weight made climbing more manageable, but Mackenzie disappointingly quickly joined Alexa in the garage for many months.

The guilt overwhelmed me in 2016 and Mackenzie rides per week finally increased, but as I examined each ride, Strava recorded and told me, “You are not getting better.” Was I not riding enough? Was I not riding correctly? I repeated familiar short loops and the elapsed times were steady but flat. Time to reflect.

The Basics of Biking

There are two basic activities in cycling in the mountains: bombing down a hill and climbing that hill. Veteran cyclists will add a third activity, “Grinding out the long flat road.” I don’t consider that a basic activity, but punishment2. My ideal sports must supply stimulus whether that’s that position of players on the ice rick or the real-time discovery of the perfect downhill line on the mountain.

As the return of biking occurred with mountain bikes, I found myself seeking the thrill of the downhill bomb. What is the fastest and most efficient way to get down the hill in Demo? The climb to get to the top of that hill was an annoying grueling tax followed by twelve and a half minutes of pure adrenalin. It’s your own the personal roller coaster in the redwoods. I can not recommend it enough.

My problem with these thrill-rides was two-fold: I wanted to improve, and as I looked at my downhill times to see if I was going faster, I learned I was not. As I stared at the data, I realized there is an equally important, but less measured status for the downhill bomb and that is mean time between crashes. Going faster meant the time between crashes decreases and… crashes suck. As I watched my fellow riders head into Demo, I saw from their armor and full-sized helmets and realized that they are both prepared and expected to crash and… crashing hurts.

Time for new life goals. I was not going to make up time on the downhill because I was unwilling to invest the time, money, and blood to get better at crashing, so we are left with climbing and climbing is an annoying grueling tax.

Climbing is Not an Annoying Grueling Tax

The downhill thrill is a mathematical mental combination of speed moderated by improvisation. How quickly and efficiently can I traverse obstacle X? There are ever changing unpredictable variables on your average mountain bike trail (fallen branches, tackiness of ground, rocks, roots. other riders moving at impressive speed) which means that the higher the speed, the less time you have to react to a new variable which implies improvisation is essential. High speed with successful improvisation rewards you with commensurate thrill. Until you crash.

Realizing climbing was where I was my new focus of training, I began to repeat rides with significant climbs. Repetition, right? MacKenzie and I climbed the Church Pop segment dozens of times and, like the downhill bomb, our times did not consistently improve. What’s the problem?

Mountains bikes are built for mountains. In addition to being sturdy (because crashes), they usually have shocks to allow easier traversal of complex surfaces (fewer crashes). Some bikes have front and rear shocks, but others have front shocks. Why would you want just front shocks? Energy transfer.

As I carefully watched the mechanics of climbing, I felt how much energy I was transferring out of my body through the bike and into the road. Shocks are designed to absorb energy, and while the goal of these shocks is to absorb the energy of the fork and frame rapidly adapting to a rough trail, it also absorbs some of the energy of pedaling. With each pedal, a small percent of my work is unhelpfully eaten by the shocks. A mountain bike without a rear shock is called a hardtail and while a bumpier ride, it’s superior at efficient climbing because it provides better energy transfer.

My second realization regarding climbing also involved energy transfer: the gearing. Mountain biking often involves steep complex climbs which means you need a very low gear that allows you to climb these grades consistently and slowly. That’s great for a steep climb, but for me, it was a crutch. When a climb became hard, I’d drop to the lowest and least efficient gear. It was easy to climb, but it did not allow me to improve.

Time to buy another bike! Enter Isabelle. On a recommendation from friends, I purchased an Open UP gravel bike. She’s a gravel bike that combines a road riding position with clearance for mountain bikes. Slightly larger and knobby tires make perfect for the roads and trails in the woods. She weighs a feather over 19 pounds, and she’s geared for climbing.

During my first Isabelle ride up a familiar climb, I slowly geared down as the climb worsened. I was alarmed when I could suddenly gear no lower. At the lowest gear, each turn of the pedal was a tremendous effort. Did I buy the wrong bike? This is about to be an expensive lesson.

So I stood up.

A couple of critical differences between the Mackenzie (the Santa Cruz 5010) and Isabelle (the Open UP). Not only is Isabelle six pounds lighter, but she also has drop bars. Those are those curvy handlebars found on road bikes. Drop bars offer you three different hand positions: dropped (the lowest position), hoods (just above the brake mechanism, and tops – just to the right and left of the stem.

All of these positions keep your arms and body more central and compact than Mackenzie’s wide mountain bike handlebars because Mackenzie is designed for high fidelity steering to allow to avoid obstacles that create crash-worthy situations. When you mountain bike, you want moment-by-moment fine-grained control of where you are headed, and wide handlebars give you a high degree of control.

Coming from years of mountain biking, drop bars initially feel like a loss of steering control, but they quickly make up the difference in, once more, energy transfer. With Isabelle gearing forced me to stand up, I felt the weight of my entire body behind each pedal. Every single bit of expended energy efficiently transferred out of my body through my legs through the bike and straight into the planet Earth.

The reward? Immediate and impressive gains on climbs where improvement had stalled for months.

The Climbing Math

Stimulus: my requirement for any sport. The mind-numbing inanity of a stationary bike or standing in place lifting heavy things is the reason I stopped going to the gym years ago. Biking provides an immediate visual upgrade with the ever-changing scenery of the forests of the Santa Cruz Mountains, but isn’t climbing the same hills time and time again… boring?

If the downhill thrill is How quickly and efficiently can I traverse obstacle X?, what’s the uphill equivalent? I’m glad you asked. The uphill thrill is a study in attention to detail including:

- What is the current grade of the climb and it’s length?

- What is my current heart rate?

- How much energy do I have remaining in the tank?

- Finally, how much of that energy can I spend on every… single… pedal given the current hill, heart rate, and remaining energy?

How does this mental and physical stimulus compare with the roller-coaster thrill of the downhill bomb? First, there’s less blood. Second, there is the zen thrill in both defining a system and then working to refine it. As each descent represents an opportunity to find the perfect line through an ever-change set of obstacles, each climb represents a chance to find the optimal climbing solution. For me, now, a good climb is when I feel I’ve spent every single calorie efficiently.

The Positive Feedback of Improvement

Strava records the change in my climbing ability for the last six months, but more importantly, I feel the difference. Impossible wheezing anaerobic hills become afterthoughts. 10-mile rides became 25. Since January 2018, I’ve biked 800 miles and climbed over 90,000 feet. Since January, I’ve bled less.

I know when I’ve properly exercised when I got to bed. I close my eyes and I automatically replay the day’s exercise. It used to be the running trail ahead then it was hockey. I’d replay goals I’d scored seeing the seconds before the puck hit the back of the net. Each move in vivid detail.

These nights when I close my eyes, I feel the handlebars in my hands and my position over the bike. Looking ahead, I see a climb through a stretch of redwoods. It’s long, I can’t see the end, and it looks like 8% grade. I’ve been biking for almost two hours. What’s my attack? How much is left in each of my legs? How much can I spend on each pedal? My brain loves this math because the thrill is in the details3.

- My Strava profile. ↩

- Avid bikers and those who finish this piece will understand the long flat grind contains the same thrills of efficient climbings, It’s just… so boring. ↩

-

Rampant accessory acquisition is a sure sign that interest in becoming an obsession. I humbly present my current necessary accessories for a good gravel or mountain bike ride:

- The Garmin 820 lives on my handlebars and provides various stats during my ride. You can install different screens and my favorite is the Edge520Visual because it shows a clear graph of historic heart rate which is my primary measure of effort.

- My outfit is a function of the weather, but there is some combination of socks, bib/shorts, undershirt and a jersey. I like biking when it’s raining and it’s very easy to stay dry in such conditions. Rapha is featured prominently and proudly.

- Shoes. Isabelle has clip-ons. So Shimano. For Mackenzie the mountain bike, no clips-ons because crashes, but super tacky shoes.

- A bright orange helmet because being super visible on roads with cars strikes me as a winning strategy.

- Black glasses. Maui Jim. Sturdy. Oakley’s for when it’s shadowy.

- For the long rides Skratch gels and Kind bars. I like the sea salt chocolatey ones.

- Two bottles of water. Both with three scoops of Skratch or Gatorade in a pinch.

I went through the exact same thing (waning interest due to not getting better) through 2015 after a decent 2014. I spiked the drop-off by buying a road bike, and it did the exact same thing you describe – interest up for a bit, and then the same sinking dread of churning miles just to get better at churning miles.

I picked up a subscription to Veloviewer, though, and that gave and gives me something to pick at. There’s any number of stats on offer and achievement stars to tickle my gaming itch. Most recently I’m trying to widen my explorer score stats, I’ve got a couple of unexplored squares that’ll push out my area of predation once cleared.

Highly recommended for adding more numbers to your cycling.

Added the Strava profile. Veloviewer is amazeballs.

I also started on the mountain bike and now ride mostly on the road.

I never got into gravel. I participated in a gravel race and group rides, but I always felt it was not as much fun as either road or mountain.

I’m a fan of climbing. Having a commute home with at least 300m of climbing helps.

How about a link to your Strava profile? 😉 I also have s veloviewer subscription like Craig.

A few weeks ago I thought about suggesting a cycling channel in the slack community, but I obviously never did.

Motivation is the key but you have to be careful that the motivational hooks you’ve chosen are sustainable. In my experience, relying on improving Strava stats is not sustainable – you have to look beyond that to the realisation that cycling makes you a better person because you are happier, healthier and more emotionally stable when you ride regularly (speaking for myself here). I’m a better husband and father when I cycle regularly due to the mental benefits cycling provides to me. I’m also physically healthier which is important to me. I always keep this at the back of my mind as the “real” motivation for cycling. I’ve also made cycling as routine as brushing my teeth. I do 2 group rides mid-week (6am), one hill session at lunch with some work mates and 1-2 weekend mountain bike ride at my local trails. I look forward to every one of those rides but for different reasons. I still check my Strava times but no longer hang-off them as “the reason” to do the next ride. At 48 I’m not going to be getting much faster but my times are still improving, mainly due to moving up to faster groups in the bunch rides and including the 800m of hill reps at lunch – which is just a bonus as I know they’ll eventually get slower again as I move into my 50’s. I look forward to this.