The last winter in the United States was goofy. While a majority of the USA was completely frozen, California spent a good portion of the holiday with terrifyingly warm temperatures. We’re talking shorts and flip-flops on Christmas. Now, if you were frozen, you are wondering why I say it’s terrifying. It’s because I am my own best weather station. The fact there was no rain for months in a state that leads the nation in production of fruits, vegetables, wines, and nuts, no rain isn’t bad because my plants are dying, no rain is a historic disaster on many levels.

Having lived in California for my entire life, I was panicky about the weather forecast in early December. When the forecast remained sunny and clear for weeks and weeks when it should be cold and pouring, I become increasingly concerned. Problem is, in the Internet age, we have worldwide satellite imagery at our fingertips that gives a firehose of data down to the micro-climate, but weather prediction – and specifically weather apps – still blows.

Give Them a Break

Let’s first give weather people and weather apps a break. It’s a matter of unreasonable expectations combined with a very hard problem. What your average weather information seeking human is looking for is the answer to a very specific question, “Please tell me with high certainty this specific weather-related fact for this extremely specific location (like where I am standing right this second) and predict this specific fact in this location for every single moment for at least five days in the future.”

These facts, this forecast, in the modern age is built using a combination of computer-based models that describe the atmosphere and a generous dose of human input that is required to pick the best possible forecast model based on pattern recognition skills, knowledge of model performance, and knowledge of model biases. Sounds hard, right?

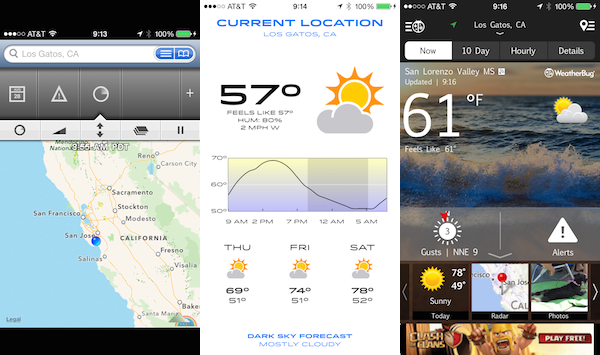

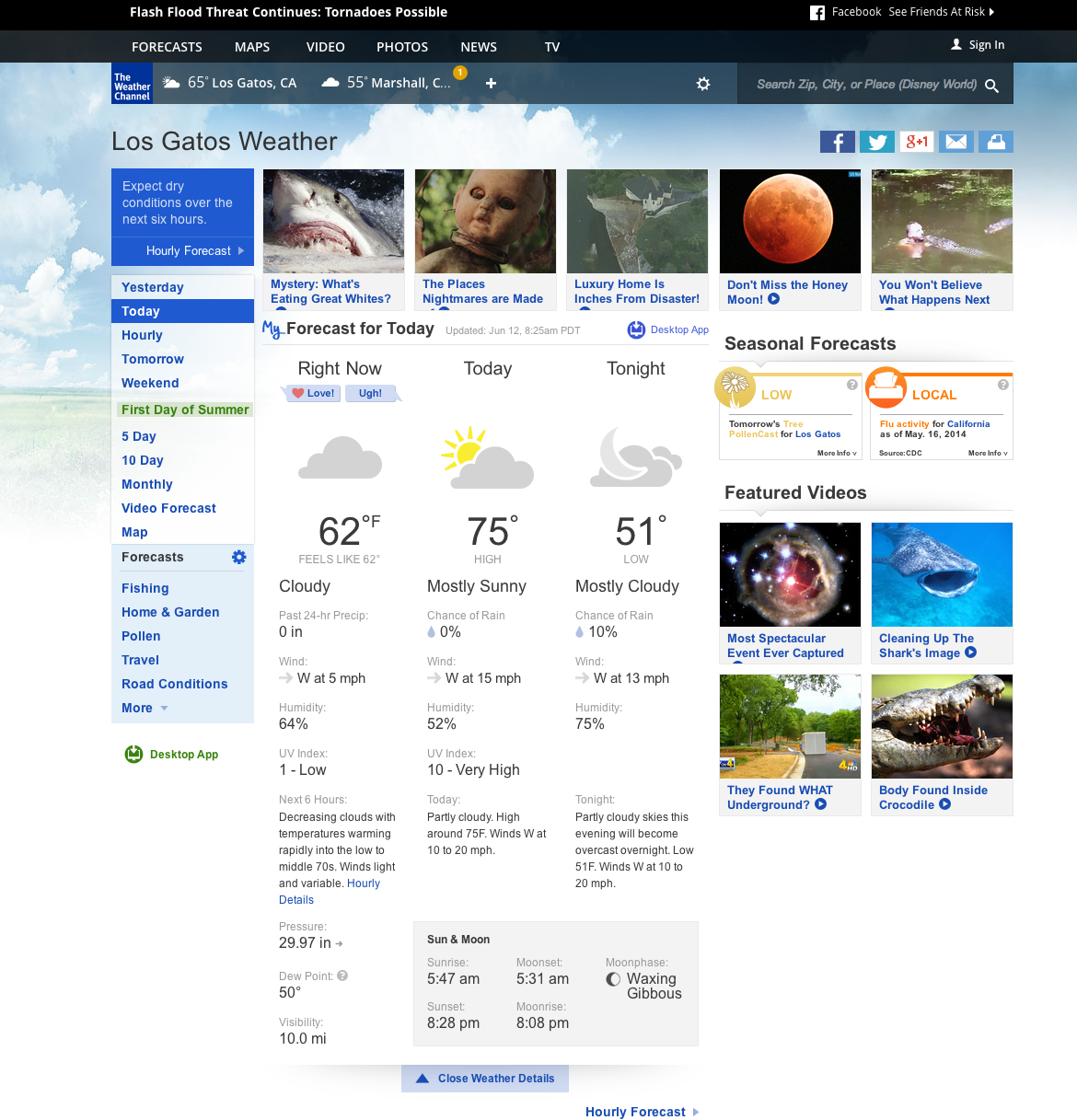

Even with all of this amazing technology at our disposal, the tried and true approach for figuring out the current state of weather is, well, looking outside. Attempting to determine what might occur at your favorite location likely involves your favorite weather website where you look for the basic forecast. For a more complete forecast, you might have downloaded a weather application and it is here where the unreasonable request of impossible data results in some of the, well, varied application design that you’ll find in iOS.

There are well-intentioned engineers and designers behind each of these apps, but this is collectively a design mess. Still, when you understand they are trying to competently answer every impossible question using incredibly complex data for humans who are used to the Internet knowing everything, you can cut them some slack.

Persistent High Pressure

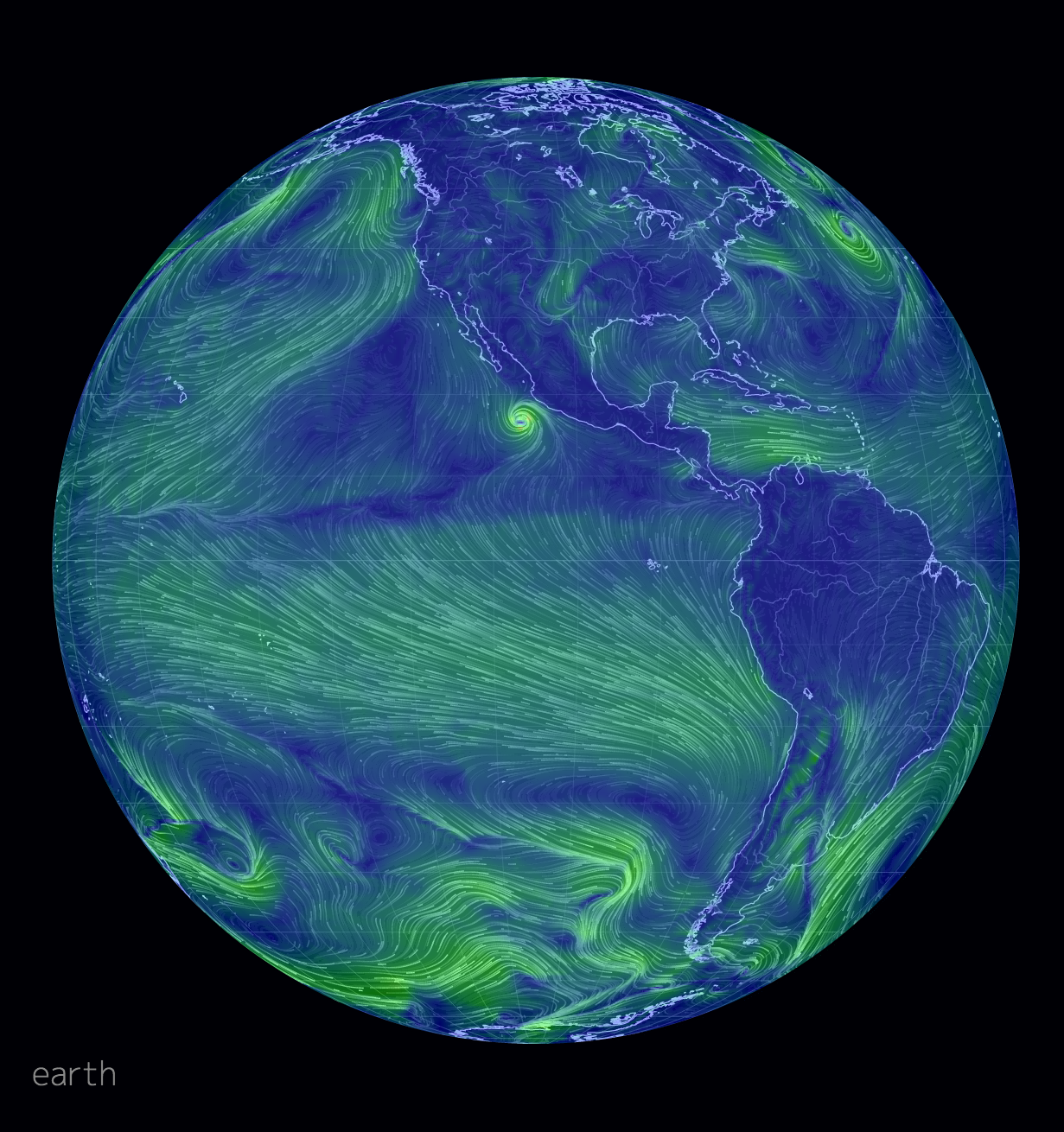

It was during the long winter of no rain that I started to look for new online resources that didn’t explain how long we were screwed, but why. It was the Dad who found Earth Wind Map and it was during California’s long dry spell that I kept returning. Take a look:

What this more current image doesn’t show is that during the long dry spell there were these incredibly persistent high-pressure regions parked over the Pacific Ocean off the coast of the northern US states. These regions were keeping whatever potential weather was being created circling up there around Alaska while we Californians worked on our tans while wrapping presents. Whenever a 10-day forecast would talk about potential rain, I’d fire up Earth Wind Map and confirm, “Is there a chance?” High-pressure region not moving? No chance.

Earth Wind Map is built on public data using off-the-shelf open source technology to visualize one set of very complex data: how is the wind moving around the planet? That’s it. No precipitation. No temperature. Just the wind. Compare Earth Wind Map with this:

Earth Wind Map elegantly deploys a common design principle of simplification. It’s just… the wind. There are lots of knobs and dials you can tinker with on the site to look at different aspects of the wind, but the front page is a well-designed visualization about wind. It does not tell me how windy it is where I’m standing right now, but it turns out those wind patterns are the ones which are going to push precipitation one way or the other. That’s useful information, but I need more to get answers to my unreasonable questions.

Rain Soon

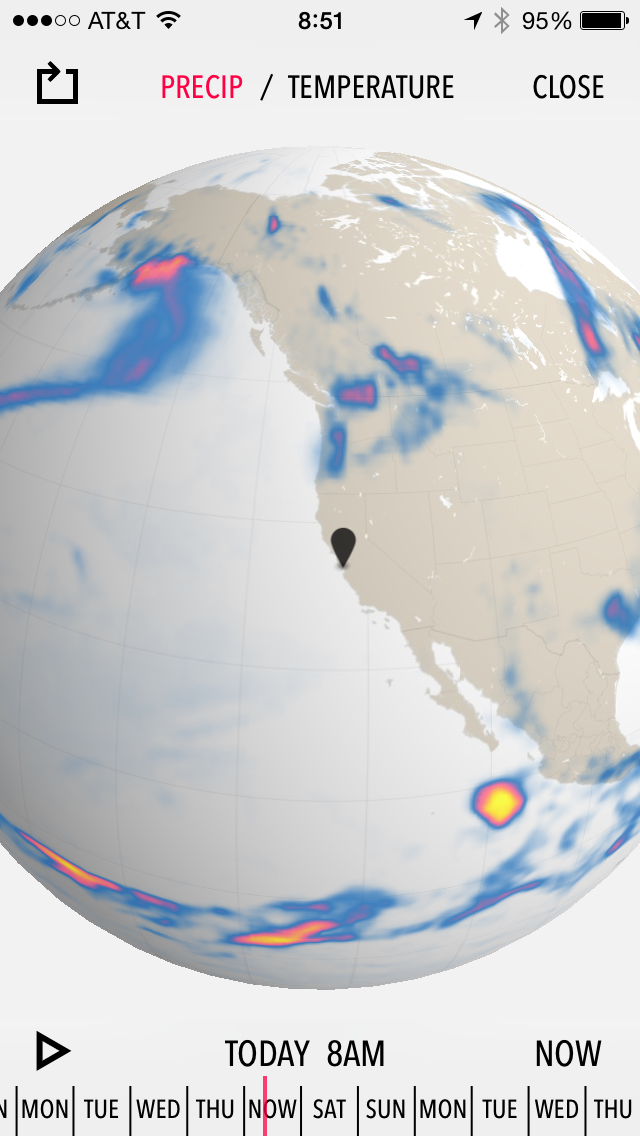

The Dark Sky weather application started as a kickstarter project with a simple goal: using my precise location, tell me when it will rain and for how long for the next hour or two. The killer feature in the initial release was a notification. Several minutes before it started to rain where you were standing, Dark Sky would notify you, “Rain soon.”

Let’s be clear. With this notification, Dark Sky was only doing slightly better than you sticking your head outside and looking at the sky. You weren’t going to better build your day around a comprehensive forecast, you mostly were better prepared for a real time decision regarding whether or not your upcoming walk would involve an umbrella.

But it felt like magic. Your phone would vibrate, you get a text from Dark Sky that read “Rain soon” and soon there would be rain. Dark Sky employed the same approach as Earth Wind Map – build one thing well. Build trust by answering one question elegantly.

Now, subsequent versions of Dark Sky have expanded their feature set to include additional features including a five-day forecast, but it remains my go-to weather application for its beautiful neon map, which shows rain for a brief window in the past and future. I don’t know if Dark Sky answers your questions, but it has begun to answer mine.

Curate Your Curiosity

I’m delighted to see the vast array of weather applications being shipped and, chances are, I’ve seen each and every one. The apps that remain on my phone are similar in terms of design philosophy: they’ve chosen to answer a few questions elegantly… beautifully.

More importantly and completely unintentionally, their intentional sparseness requires me to care more about what I’m asking. Weather prediction is a complex problem sitting on top of an ever-changing pile of even more complex data, and the more you understand this complexity, the more informed your questions.

I don’t need weather apps to answer all my questions. I need them to quickly, reliably, and elegantly answer a handful of questions. Combined, these answers start to draw a picture that I can only complete by being endlessly curious. It’s the best strategy to find answers to my endless unreasonable requests.

I believe Dark Sky is using the API at http://forecast.io for its information.. I’ve been hooked on forecast.io ever since i found it.. Good information, Great design..